Fleeting Images: Matías Piñeiro on You Burn Me

Critics Campus 2024 participant Daniel Tune speaks to director Matías Piñeiro about the aesthetic and thematic departures in his latest work, and how cinema can communicate the pleasure of encountering time-honoured texts.

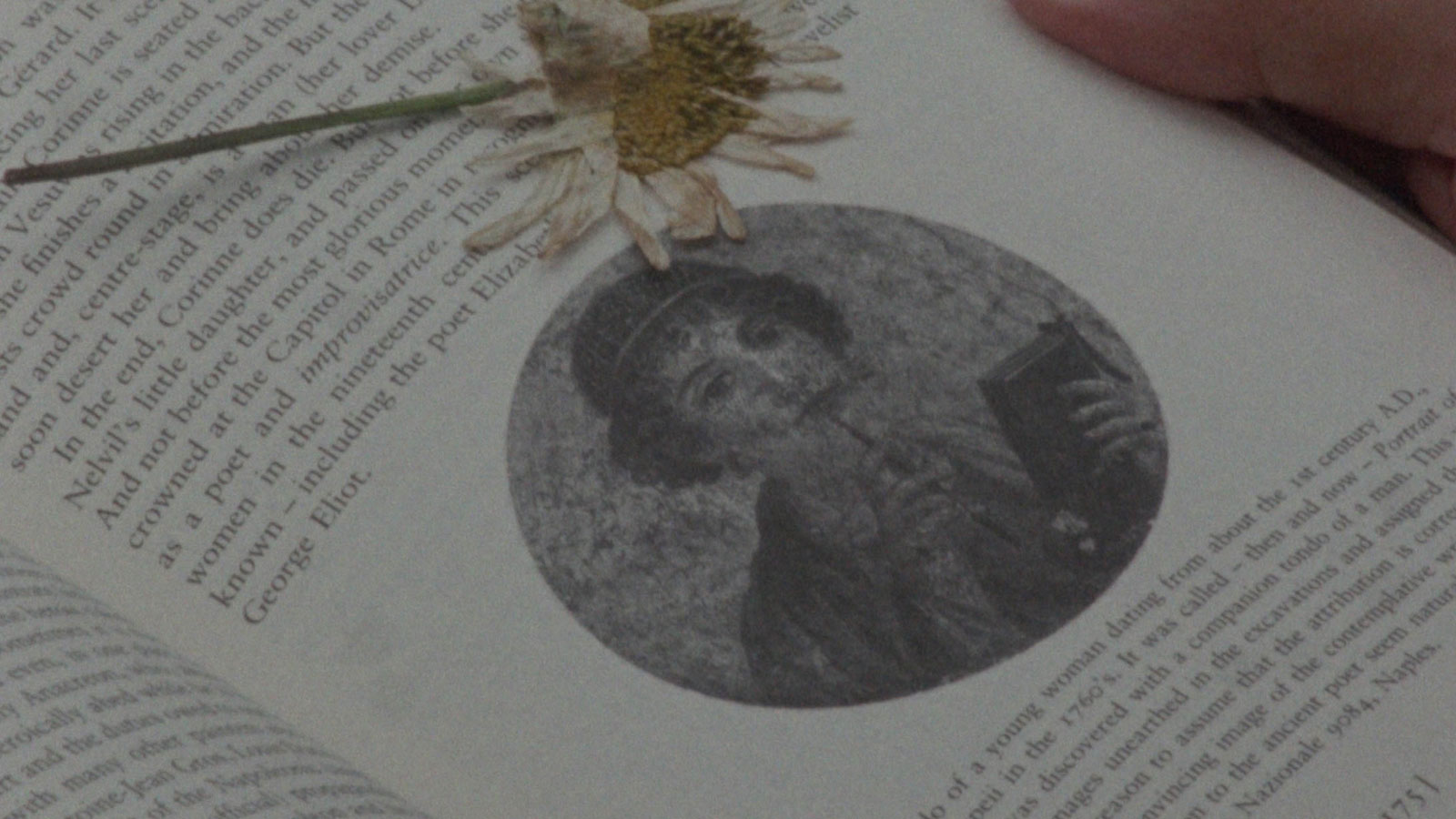

The films of Matías Piñeiro are luminously idiosyncratic. Fascinated by the textures of language and everyday life, his modestly produced films are breezy in tone yet dense with oblique meaning. His slippery new film You Burn Me is a continuation of his career-long fixation on text, incorporating elements of “Sea Foam” – a chapter from Cesare Pavese’s 1947 book Dialogues with Leucò – and surviving fragments of Sappho’s poems into a labyrinthine reverie on the distances that define life, art and time. I spoke with the director about a cinema of reading, the need to lose control, and the joys and challenges of making cheap films with friends.

There’s a stylistic shift in this new film from your long run of Shakespeare films. You’ve moved from shooting digital long takes to a 16mm look that is more based on montage. What motivated this change?

I think the shift has to do with using different material. The Pavese text is much denser and more melancholy than the Shakespeare texts I was working with, so the breezy style I had established with those films wouldn’t work. I felt I instead needed to expand the text out, like a sponge in water. I decided that I would do this by incorporating the footnotes of the text into the structure of the film.

This was when the 16mm Bolex camera appeared. For a long time, I was very resistant to shooting on film – I thought it was a bit of a rich-person thing. But when I discovered the Bolex, I realised it would give me this limitation, because it only shoots 25 seconds at a time. So it would force me to make a film of fragments, which helped form the footnote structure. But it also related to Sappho, whose work only exists as fragments. The Bolex helped to create and enforce these choices, which would be impossible to do with digital; without the limit, 25 seconds [per] take would feel fake. So it helped me to not be in full control.

That’s interesting that you say that you like limitations on your own control. You obviously pay a lot of attention to form, but there is an organic, even chaotic quality to your work – what interests you about this state of being both in and out of control?

Well, I became interested in cinema because of [Alfred] Hitchcock – the controller of the universe! So obviously I like form and control. I get excited by the magnetism that it gives to the world I’m portraying. But I feel I need something pushing back against this, because I am a little bit stubborn, and sometimes my ideas are a little silly. So I want something that transforms the film into something more intersectional and multilayered. I want to be surprised by the films, I want something that is not just me to appear in them. And because I don’t have to do them in three weeks, I have time to find and develop those things as I make it.

You Burn Me

Your cinema is always closely engaged with literary sources, though the films are not exactly adaptations. Literature is often thought of as being cinema’s opposite – calling a film ‘literary’ can be a criticism. What draws you to making films about literature, and how do you make literature cinematic?

I think that what attracts me from the text is the actual reading experience – I less adapt texts than try to embody that experience. I like the joy of finding something of yourself in reading, especially in these texts that are so far away from my own life. I don’t have anything to do with Sappho, Pavese or Shakespeare; but because they are so distant, the little coincidences between them and me seem to resonate louder. I think the joy and curiosity of these resonances is something that can be shaped into cinema. My hope is that, in shaping and sharing the reading experience in this way, the viewer experiences some of that joy and curiosity as well. Or, if they find it obscure, they are at least challenged by a movie that tries to do different things.

It’s interesting you talk about the potential for viewers to find your work obscure. Do you worry about your work being misinterpreted?

I don’t care, really. You can drift in my films; there’s no need to completely understand every sign that I put in. I think that the viewer makes their own path. That’s why I want the films to have things that come from something other than me. I think it is too oppressive for me to dictate every viewer’s response. It needs to be a little alternative, so that there is room for the viewer to put something of their own in. I need a viewer who wants to enter a dialogue, and not be afraid of feeling left behind sometimes. It’s a movie, for god’s sake, not science.

You’ve always worked with very low budgets and a crew of regular collaborators. What about this mode of filmmaking appeals to you?

I’m fortunate that I like to make small films with a small group of people. So one film can end up financing the next, and the people who work on the movies can stay the same, because everyone enjoys the process and is happy to just keep the balance, even if they aren’t making a lot of money. It can sound a little bit hippie when I say it like this, but shooting is always tough. Working with friends is kind of more responsibility, because there’s more at risk when tensions come up. But something does happen in working with the same people over and over.

Having less connections with money also helps me not to get confused and make better decisions. If you go a more traditional way, you have very little shooting time, and you cannot change things so much. But I need to be able not to know, to have the luxury of time and the freedom to change. A lot of the ideas in my films aren’t there when we start production. But working independently and without deadlines, you can live your life and make choices – and some continue, and others don’t.